Wow. In a modern laboratory in the picturesque Swiss city of Veve, scientists are carefully administering the nutrients needed to keep tiny clumps of human brain cells alive.

These tiny brain clusters, called mini-brains, are now being used as early computer processors. But unlike normal computers, they cannot be restarted after death. Therefore, their health is very important.

This amazing research area is called biocomputing or wetware. It aims to harness the unique and mysterious computing abilities of the human brain. Fred Jordan, co-founder of Swiss start-up company FinalSpark, says that in the future, processors made from brain cells could replace the silicon chips that power artificial intelligence (AI).

Today’s supercomputers use silicon semiconductors to mimic neurons and their networks in the human brain. But Jordan said, “Instead of trying to imitate, let’s use real brain cells.” ’

Biocomputing also holds the potential to rapidly reduce the energy consumption of AI tools, which is now becoming a challenge to climate goals globally. “Biological neurons are about a million times more energy-efficient than artificial neurons,” he said. Unlike the powerful chips made by companies like Nvidia, these neurons have the advantage of being continuously reproduced in the lab.

But there’s still a long way to go to compete with the cutting-edge hardware that drives the webware technology world. At the same time, an interesting question arises: Can these tiny brains ever be conscious?

Brain Power and Manufacturing Process

FinalSpark first buys stem cells to make its bioprocessors. These cells are basically human skin cells, which scientists then transform into neurons and collect them into small millimeter-sized clumps called brain organoids. These clusters are similar to the brains of fruit fly larvae.

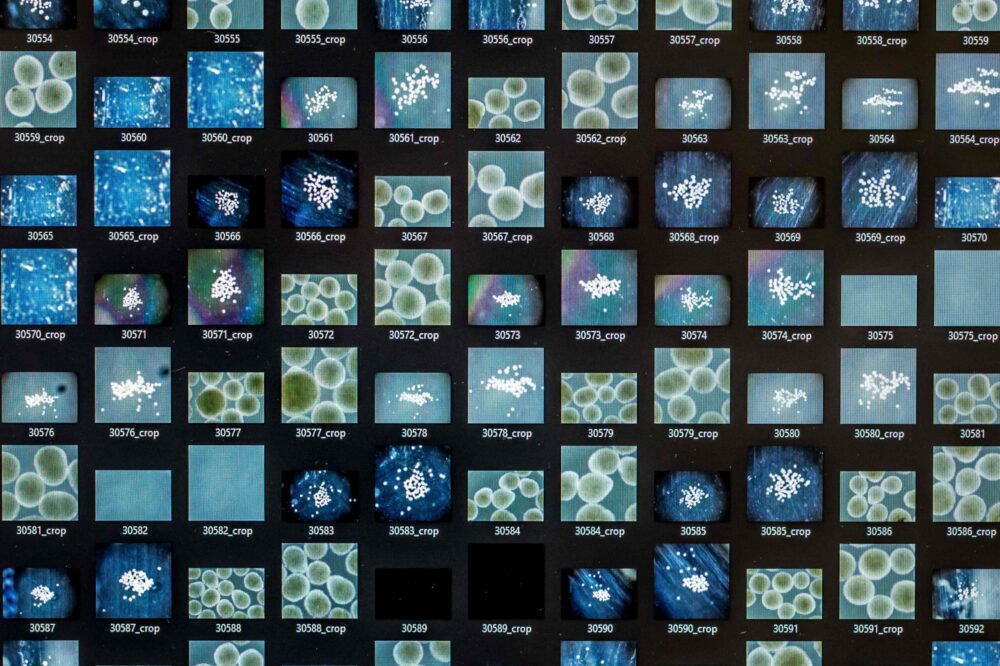

In the laboratory, electrodes are connected to the organoids, which allow scientists to listen to the “internal communications” of these neurons. Also, when organoids are stimulated by small currents, they respond by increasing activity – comparable to the ‘one’ or ‘zero’ signal of traditional computing.

Currently, ten universities around the world are conducting research using FinalSpark’s organoids. Live views of the working neurons are also available on the company’s website.

Benjamin Ward-Cherrier, a researcher at the University of Bristol, used an organoid as the brain of a simple robot, which was able to distinguish different Braille letters. “Converting data into something that organoids can understand and interpret their responses is very challenging, much less working with robots,” he said. ’

But since organoids are living cells, they can die. Ward-Cherrier’s team had to start again after the organoid died in the middle of an experiment. According to FinalSpark, the lifespan of an organoid is about six months.

Lena Smirnov, a researcher at Johns Hopkins University in the US, is using similar organoids to study brain conditions such as autism and Alzheimer’s disease. He says that although biocomputing is now the “first accessible technology used for biomedical research”, it could change significantly in the next two decades.

Can organoids be animated?

All the scientists AFP spoke to have ruled out the risk that these tiny cellular brains could be leading to the development of consciousness. “This is a matter that falls within philosophy, so we’re working with ethical experts,” Jordan said. ’

According to him, these organoids do not have pain-sensing receptors and have only about 10,000 neurons, which is very small compared to the 100 million neurons found in the human brain.

With the mystery of the origin of the human brain’s consciousness still unsolved, Ward-Cherrier hopes that biocomputing will provide a deeper understanding of how the brain works in the future.

Returning to FinalSpark’s laboratory, Jordan opened a large incubator with a complex network of tubes. There were 16 brain organoids preserved.

As soon as he opens the door, the lines on the screen suddenly start to spike — which shows the activation of neurons. According to the scientists, there is no known mechanism by which these cells feel that the door has opened.

“We still don’t know how they’re going to find out if they’re going to open the door,” Jordan said with a smile. ’

प्रतिक्रिया दिनुहोस्